Off the west coast of Scotland in the small village of Crinan, artist Nick Smith has spent every day of lockdown studiously creating new art. With a show in New York postponed and traveling to the States for research currently on hold, Nick is using this time to create and reflect on the direction of his future work.

After the success of his ‘Purgatory’ show at Context Art Miami last December, Rhodes Contemporary is delighted to announce Smith’s return to the gallery this winter, with a new series of works, currently titled ‘Pioneers’, exploring and remastering classic American masterpieces.

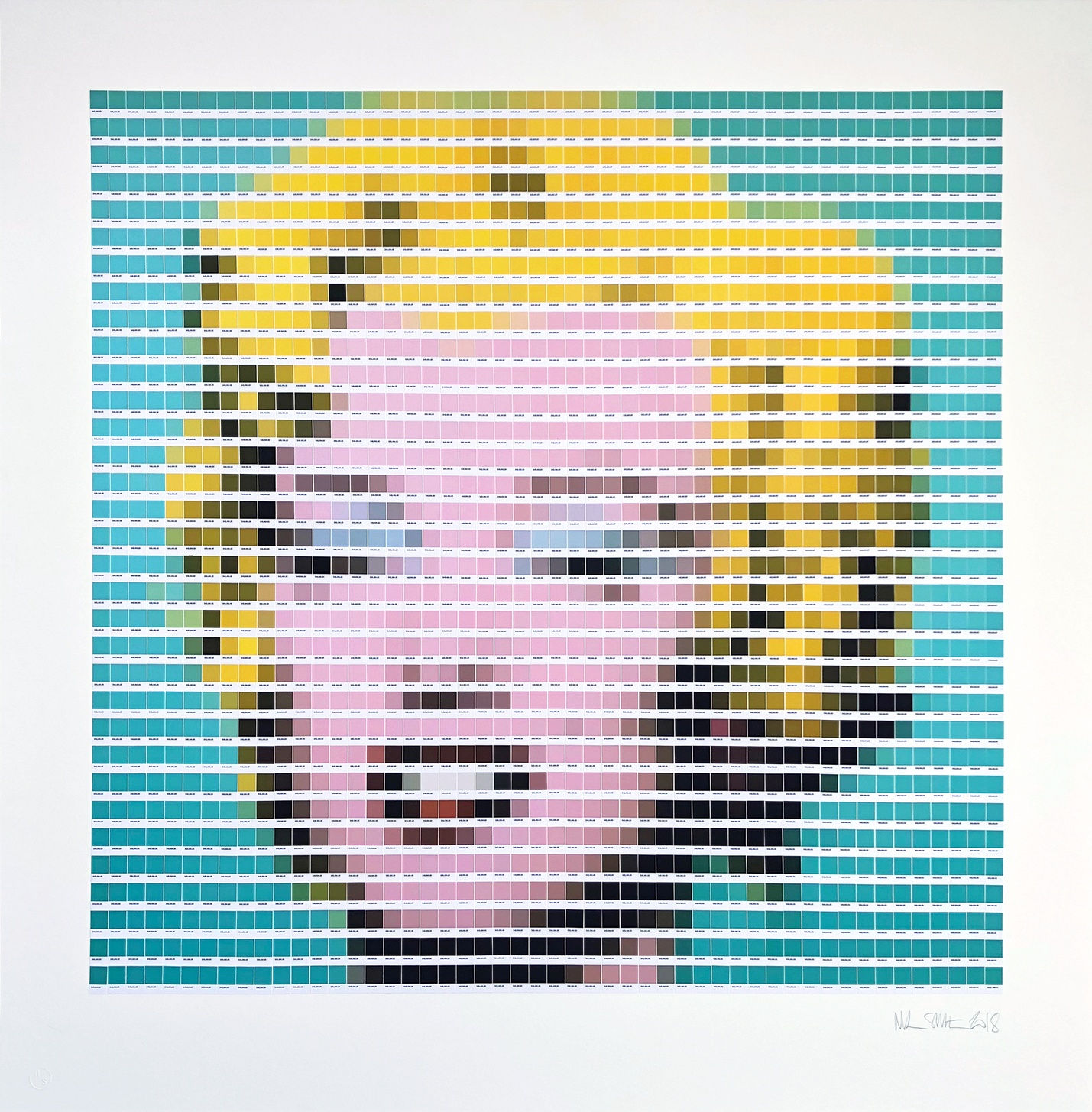

In this series, Smith returns to an original method of word-colour association, which we first saw with his 2015 ‘Psycolourgy’ series. ‘Pioneers’ will explore the iconic artwork and popular culture of North America, a place Smith has had a fascination with since early childhood, remembering friends returning from holidays from the States brandishing the exotic and glamorous American fashion labels.

“Everything is just bigger”, from the trucks to the people, jokes Smith. American culture has always been a source of intrigue to its British cousin, and with the growth of media and the internet, American culture, fashion and music have made their way across the Atlantic into British mainstream media and consciousness and continues to be a source of inspiration for artists.

As an ‘Americanophile’, the country has great resonance with Smith, and much of his work ends up in the states as his American market continues to grow. ‘Pioneers’ feels like a natural progression to his P-series, whilst also paying homage to his earlier word-colour association technique. Collaging Warhol’s ‘Marilyn’, Keith Haring’s dog and Nike sneakers, unconsciously or not, his work definitely takes inspiration from North America, which will be delved into further in this latest body of work. Whilst you can expect to see iconic works from the lexicon of American paintings, such as ‘American Gothic’ by Grant Wood, Smith is also interested in reworking some of the lesser-known pieces.

Smith not only plans to rework paintings, but also the products, packaging and literature that has come out of America. Experimenting with the original publications of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962) and Catch 22 (1961). Smith prefers pre-owned copies, as their patina of wear creates an interesting aesthetic.

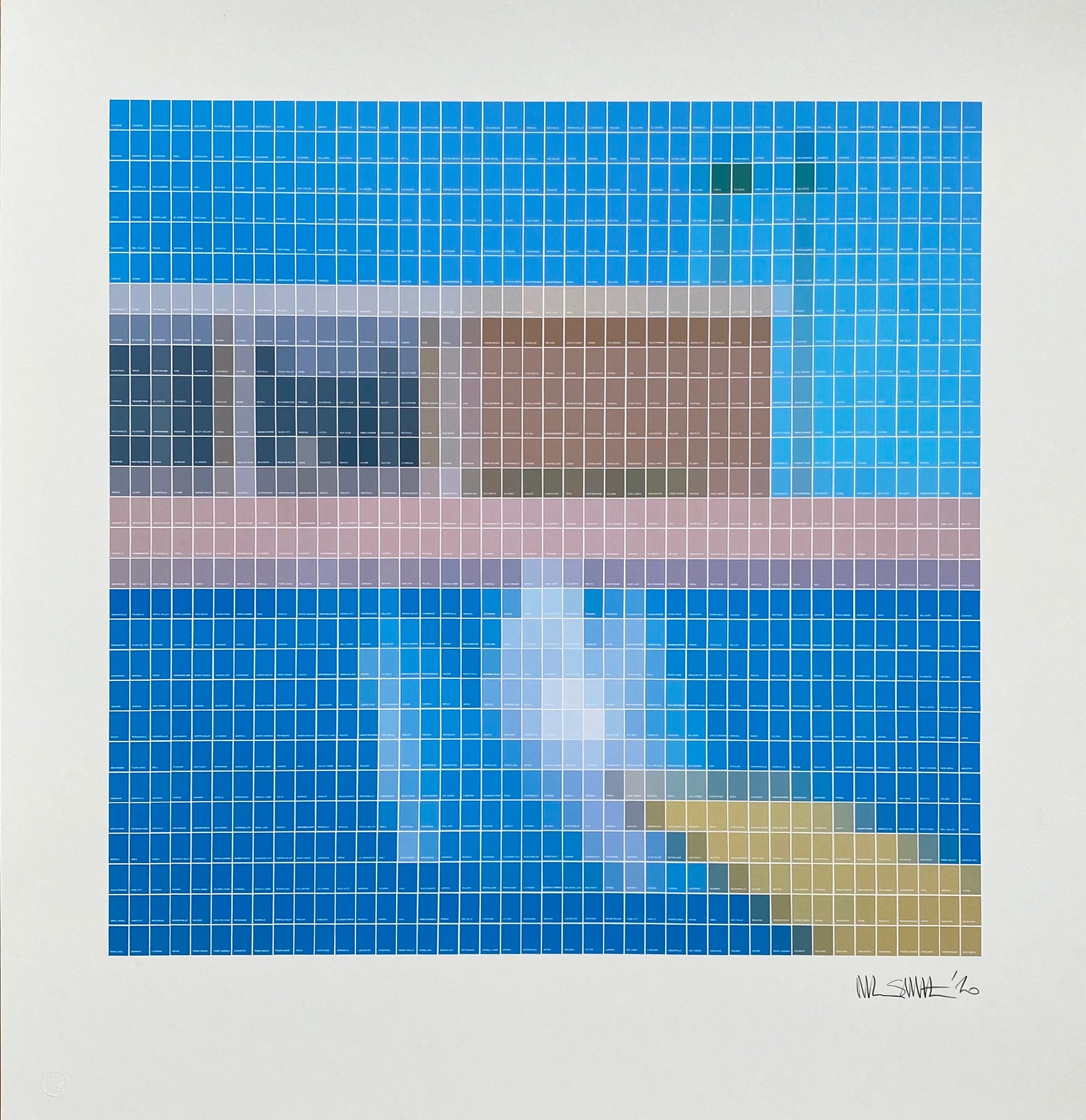

An earlier career in interior and graphic design has allowed Smith to approach concepts with a unique visual style, usually unpacking complex art-historical, social, and psychological ideas and theories using single words on ‘chips’ synonymous with colour swatches. Earlier this year, Smith experimented with removing the white strips on the colour chip to create a more pixelated image.

Marrying stunning visuals with a layered textual narrative, the concept remains at the core of Smith’s artistic vision. The work’s aesthetic beauty is almost secondary or a natural bi-product, not the raison d'être. Smith compares his process with following a design-brief or question, spending a lengthy process developing and researching the concept, so as to satisfy his design instinct and to avoid veering into the world of contrived ‘art for art’s sake’.

The multi-layered complexity of his work succeeds in inspiring discussion and debate. To take his 2019 ‘Pinched’ series, which explored stolen paintings, and cultural loss can simultaneously increase the work’s notoriety and value. At London Art Fair earlier this year, an impressive work measuring approximately 1.5 x 2m, (‘Rembrandt - The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 2019’), was met with awe as people dragged their friends excitedly to recount the epic story behind the theft of the original Rembrandt work, the date of its loss cleverly documented under each colour-chip. This collage series of recognisable masterpieces, can each be read as mini art-history essays on the greatest stolen-art heists and have become speaking points in which to navigate through larger conceptual ideas or to spark relevant anecdotes.

Smith admits to having a fascination with conspiracy theories and alternative truths, listening to various theorists whilst he works and confesses to “never taking things at face value”. This hardly seems surprising when faced with his work which plays with image recognition and is full of obscured messages. The pixelated form feels almost investigative, like a police CCTV image, see ‘Theft of Banksy CCTV - (Microchip), 2019’.

“I do believe that there is an over-arching narrative in this world that isn’t as obvious as we might think.”

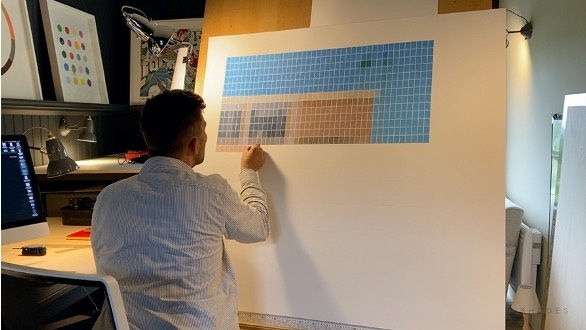

The original artwork is broken down into its smaller components, where its core elements are extracted with microscopic accuracy. The clinical approach and dexterity which Smith applies to his practise - hands clean, scalpel-sharp, paper uncreased, using tweezers to place each chip, (see his microchip series) is where we see a glimpse of Smith’s ambitious and disciplined personality.

Reflecting on the evolution of his method, Smith grimaces at the carelessness with which he made his earlier works, with overlapping tiles creating uneven negative space. However, the naivety of his earlier works documents the development of his career, to the works current exquisitely disciplined and precise form. After relocating to the rural farmland in Scotland, Smith speaks of the artistic freedom this has allowed him, where he now works in his specialised studio space.

Whilst conspiracy and myth infiltrate the work in the studio, myth, and appropriation are also fundamental to understanding Smith’s unique artistic style. Appropriation is a distortion that maintains but shifts the former connotations to create new signs, symbols, meanings in a covert way. Smith appropriates icons of classical European art - the works of Leonardo Da Vinci and Van Gogh - joining image and caption into either a complimentary or subversive but powerful combination of mutual appropriations, allowing the viewer to contemplate the word-image constructions.

To return to the ‘Pinched’ series, ‘Klimt - Portrait of a Woman, 2019’ derives potency from its associations with Klimt’s original painting, which is repositioned by Smith, within another context - its theft and the mystery surrounding its very existence, which up until recently, had remained unrecovered.

Smith’s visual/verbal constructions invite the viewer - first at a distance, forcing them back to visually understand and process the pixelated image, or through a phone, which so happens to crystallise the image. Then the small text pulls the viewer forwards, to the point where the image is abstracted but the words become readable, inducing a sort of frenzied ritual yo-yo-ing motion.

Now that galleries and art fairs are transitioning to exhibit online, with virtual viewing rooms utilising the latest 360-degree viewing technology, we are looking at a future industry void of human interaction and physical experience. But for many artists, physical proximity with their work is critical to understanding it. Smith’s work requires it. The interconnected relationship between image, text and audience requires an unconsciously physical response from the viewer- both viewing from afar and reading up close to make sense of the pixelated image. Smith’s work demands you to get up close with it, a refreshing and frankly relieving concept many of us are pining for. The corporeal response to Smith’s work provides hope in a progressively digitised and isolating world.